Roads of Adaptation: the Role of Winter Roads in the Northwest Territories

Driving along the paved, all-weather highway from Alberta to the Northwest Territories’ capital of Yellowknife is an experience similar to the one found in most areas of southern Canada. But what is hidden from drivers, unless they take the turn at kilometer 239, is a whole other kind of infrastructure; one specifically built for the harsh and frozen surroundings of northern winters.

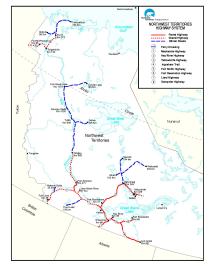

This is where the Tlicho Winter Road corridor begins: a seasonal network of roads built only of snow and ice, connecting the otherwise isolated communities of Whati, Gameti, and Wekweeti to the territorial highway system. These roads are an example of the 1,450 kilometers of public winter roads built annually in the NWT and which, when combined with private winter roads such as the Tibbitt to Contwoyto road discussed later, form the territorial winter road system. Following a practice used in only a handful of other countries in the world, the NWT take advantage of the harshest time of year to turn the many frozen lakes and snowed-in trails of the territory into roads that reach into the most remote parts of the region.

For communities like those in the Tlicho region located northwest of Yellowknife, public winter roads allow residents to travel and receive goods and services for part of the year at costs notably cheaper than the ones of the only other alternative, which is air service. As the only means of ground access, travelling between communities by way of the winter road is also a significant benefit for these communities. Access to a variety of other markets, as well as cultural, social, and political events, keeps community members connected to the rest of the territory and offers these communities increased opportunities to participate.

For the Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT), winter roads are a seasonal solution to the lack of all-weather roads in some regions. Construction through these areas is somewhat easier when these roads can pass through frozen water crossings, marshlands, and other terrain that are usually difficult to build over. In addition, environmental impacts from these roads are generally less compared to all-weather roads because they require less intensive maintenance and construction practices, and feature lower traffic volumes.

Those who may have heard of ice roads from watching the popular History Channel television series Ice Road Truckers, are also probably familiar with the stories of the individuals who transport supplies across these structures throughout the season. The story that is not captured on camera, but deserves equal attention, is the one about the men and women who build these roads of ice and snow. The innovative and adaptive work of these dedicated professionals is used as an example for engineering and construction practices around the world.

Winter road construction crews will often spend the coldest and darkest days of the year in small mobile camps, away from their friends and families while building these routes. With temperatures often dipping below minus 40 degrees Celsius and sunlight appearing for an average of five hours per day between late December and early January, it takes a certain tenacious spirit to brave such conditions.

In early December, the GNWT Department of Transportation’s winter road contractors and subcontractors start from each end of the route, clearing snow off of lakes and trails along the Tlicho corridor. Tackling snow plowing from both directions enables crews to “groom” the route as quick as possible. This stage is important because snow has an insulating effect. Without its early removal, the ice may never reach the thickness required for safety during the road’s operating season. Marian Lake is of particular importance for early snow removal since it is shallow, with dense organic matter and natural gases making freezing difficult.

Historically, winter road crews would drill through the ice with an auger to measure ice thickness; now, however, the standard in the Northwest Territories is to use ground penetrating radar (GPR) in a process called “profiling”, which is continually undertaken to monitor the thickness of the ice. This technology logs two measurements per meter along the center and both edges of the road. The GPR equipment is pulled on a sled behind a tracked Bombardier vehicle at 30 km/hour, making initial measurements faster than it was possible using old methods.

The advancement of profiling technology has also been essential to achieving a new level of worker safety by providing constructors with a much fuller picture of the ice’s characteristics. Although workers are still required to drill an initial hole to calibrate the radar equipment in order to ensure proper functioning, these rare times are regulated by the GNWT Department of Transportation’s publication, A Field Guide to Ice Construction Safety. Through the Transportation Association of Canada (TAC), the department has also collaborated on Best Practices Guide for the Construction, Maintenance, and Operation of Winter Roads.

For safety purposes, crew members are required to wear flotation suits and are generally prohibited from entering onto the ice surface until 18 centimeters of ice thickness has been achieved. Most equipment, other than the lightweight vehicles used in the early construction process, is restricted from operating on ice until 30 centimeters thickness is achieved.

The use of light weight vehicles, often tracked and floatable, is essential in the early stages of construction. Much of the equipment has been designed or modified specifically for the use of ice and winter road building. For instance, much of the snow clearing is done by plow-vehicles referred to as “snow cats”. These vehicles have tracks which have been designed with a wider stance for safe use on thinner ice. Lake water is sprayed onto landbased sections of the road from the rear of a “Hydrema”, which possesses an onboard tank system, while it also plows snow. Where the Hydrema is too heavy to operate, pumps are used to flood ice surfaces. Flooding promotes rapid ice growth.

The GNWT Department of Transportation begins opening the Tlicho winter road system to public traffic in stages. This begins with what is referred to as a “soft opening”, where light vehicles make their way onto the winter road. The GNWT upgrades thresholds as the ice continues to thicken, aiming for an ideal capacity of 40,000 kg at the height of the winter road season. This requires approximately 100 cm ice depth. At full capacity, a maximum speed limit of 50 km/h can usually be achieved, although this is often adjusted according to conditions. Most sections of the road are posted at a 30 km/h limit for heavy traffic.

The GNWT recognizes that overland access between the communities is an important public service and aims to keep the Tlicho system open up until the third week of March. Although each community’s section of the winter road system opens at a different time, ranging from late January to early March, in most cases the roads remain open until early to mid-April, with recent closure dates around the April 7-15 range. Safety is the first priority for the Department of Transportation and also the criteria upon which opening and closing decisions are made.

The NWT is also home to privately operated winter roads whose main function is to support exploration and industrial development activities. In particular, this involves mining, which has long been the industrial driving force in the north, and the burgeoning oil and gas industry. Unlike public roads, private roads are intended strictly for the resupply of industry operations in as quick and efficient a manner as possible.

The best-known example of a private winter road in the NWT is the Tibbitt to Contwoyto road constructed northeast of Yellowknife, off of Highway 4 that stretches into Nunavut. Within this corridor are three producing diamond mines: Ekati, Diavik, and Snap Lake. The Tibbitt to Contwoyto winter road is managed as a Joint Venture of several mining companies.

This private winter road is comprised of approximately 85 % frozen lakes and 15 % land portages. It is constructed and maintained through construction techniques similar to those used by the GNWT, with a few exceptions. For instance, in the past, the Joint Venture used ground penetrating radar profiling, completed with the use of a helicopter and an amphibious Hagglund vehicle to undertake ice profiling along the route. The use of this equipment ensures that the road reaches its maximum capacity very quickly, and resupply is completed approximately within a month. Average operating dates for the Tibbitt to Contwoyto winter road are from the first week of February to the end of March. The road requires a high level of effort to ensure its objectives are met in this short period, and consequently requires significant resources and expenditures.

In recent years, the construction and operation of both private and public winter roads have faced significant complications due to climate conditions. Increased instances of storm weather early in the winter, for instance, can disrupt the formation of ice.

At the other end of the operating season, winter road constructors are experiencing increased drainage problems on roads, with portage areas in particular becoming soft, flooded, or muddy earlier in the season. This sometimes causes interruptions in service, resulting in inconveniences to daily life in communities and costly delays for the industry. Clearly, planning for winter roads is becoming more challenging with unpredictable weather events. Increased snowfall, for instance, was mentioned earlier with its role in slowing ice formation due to insulation. Despite this, a minimum of 10 cm (or about 4 inches) of snow must still be allowed to accumulate in order to protect the sensitive terrain beneath the winter routes. Extreme fluctuations of weather conditions can cause delays in opening and increased maintenance costs for snow removal.

In the face of these challenges and changes, ongoing research and development by experts in the NWT is helping to address these issues. Already, technology such as spray-ice–the process of spraying water into the air over the ice surface in order to have it freeze and accumulate–is able to generate and hasten the thickening process. GIS-based ice data records and the use of ice log books by road workers help to establish new patterns and allow planners to better prepare for the winter road season. Caching equipment along established routes also allows workers to respond more quickly to unexpected snowfall or other climatic conditions. Finally, adaptation can be achieved by realigning winter roads off of lakes onto high ground or building all-weather roads where they now exist.

As construction practices change and adapt, winter roads continue to give back to the resilient, resourceful, and innovative people responsible for their creation by contributing to the prosperity and way of life of all Northerners.

The GNWT Department of Transportation operates, maintains, repairs, and constructs the Northwest Territories’ transportation system and is guided by a vision for the safe, secure, accessible and reliable movement of people and goods.

Hyperlink: www.dot.gov.nt.ca